CS61A Notes

This is my notes for CS61A su20.

Writeups for Homeworks and Labs are available here.

Docstring

A docstring is a string literal that occurs as the first statement in a module, function, class, or method definition. Such a docstring becomes the __doc__ attribute of that object.

- The docstring line should begin with a capital letter and end with a period.

- The first line should be a short description (summary).

- If there are more lines in the documentation string, the second line should be blank, visually separating the summary from the rest of the description.

- The following lines should be one or more paragraphs describing the object’s calling conventions, its side effects, etc.

There is a plugin called Python Docstring Generator that can generate docstring templates.

Command Line Options

-i: The -i option runs your Python script, then opens an interactive session. In an interactive session, you run Python code line by line and get immediate feedback instead of running an entire file all at once.

-m doctest <filename>: Runs doctests in a particular file. Doctests are surrounded by triple quotes (""") within functions. -v shows the details.

About ok

In 61A, we use a program called Ok for autograding labs, homeworks, and projects.

python3 ok -q <function> is a way to test a single function in this course. We can add -i option to open an interactive terminal to investigate a failing test for question.

The best way to look at an environment diagram to investigate a failing test for question is to add --trace option

To prevent the ok autograder from interpreting print statements as output, print with 'DEBUG:' at the front of the outputted line.

Expressions and Statements in Python

A sequence of operands and operators, like a + b - 5, is called an expression. Expression will be evaluated by the Python interpreter.

Primitive expressions

A primitive expression requires only a single evaluation step. Literals, such as numbers and strings, evaluate to themselves. Names require a single lookup step.

Arithmetic expressions

Arithmetic expressions in Python are very similar to ones we’ve seen in other math contexts.

Assignment statements

An assignment statement assigns a certain value to a variable name.

To execute an assignment statement:

- Evaluate the expression on the right-hand-side of the statement to obtain a value.

- Write the variable name and the expression’s value in the current frame.

Logical Expression

In Python, only False, 0, '', None are considered as False in Python. Anything else is considered to be True.

Python includes the boolean operators and, or, and not. These operatorsare used to combine and manipulate boolean values.

and evaluates expressions in order and stops evaluating (short-circuits) once it reaches the first false value, and then returns it. If all values evaluate to a true value, the last value is returned.

or short-circuits at the first true value and returns it. If all values evaluate toa false value, the last value is returned.

>>> 2 and 3

3

>>> 0 or 999

0def Statements

def statements create function objects and bind them to a name. To diagram def statements, record the function name and bind the function object to the name. It’s also important to write the parent frame of the function, which is where the function is defined.

Call expressions

Call expressions, such as square(2), apply functions to arguments. When executing call expressions, we create a new frame in our diagram to keep track of local variables:

Evaluate the operator, which should evaluate to a function.

Evaluate the operands from left to right. (Unlike assignment statement)

Draw a new frame, labelling it with the following:

A unique index (f1, f2, f3, ...)

The intrinsic name of the function, which is the name of the function object itself. For example, if the function object is func square(x) [parent=Global], the intrinsic name is square.

The parent frame ([parent=Global])

Bind the formal parameters to the argument values obtained in step 2 (e.g. bind x to 3).

Evaluate the body of the function in this new frame until a return value is obtained. Write down the return value in the frame.

If a function does not have a return value, it implicitly returns None. In that case, the "Return value" box should contain None.

Lambda expressions

A lambda expression evaluates to a function, called a lambda function. For example, lambda y: x + y is a lambda expression, and can be read as a function that takes in one parameter y and returns x + y. A lambda expression by itself evaluates to a function but does not bind it to a name. Also note that the return expression of this function is not evaluated until the lambda is called. This is similar to how defining a new function using a def statement does not execute the function’s body until it is later called.

Higher Order Function

Higher-order-function is a function that takes in another function as argument or returns a function. We can implement a general function like this:

def improve(update, close, guess=1):

while not close(guess):

guess = update(guess)

return guessThis improve function is a general expression of repetitive refinement. It doesn't specify what problem is being solved: those details are left to the update and close functions passed in as arguments.

We can use this function to compute the golden ratio. The golden ratio, often called "phi", can be computed by repeatedly summing the inverse of any positive number with 1, and that it is one less than its square.

def approx_eq(x, y, tolerance=1e-15):

return abs(x - y) < tolerance

def golden_close(guess):

return approx_eq(guess * guess, guess + 1)

def golden_update(guess):

'''

>>> improve(golden_update, golden_close)

1.6180339887498951

'''

return 1/guess + 1Newton's method:

def newton_update(f, df):

return lambda x: x - f(x) / df(x)

def find_zero(f, df):

near_zero = lambda x: approx_eq(f(x), 0)

return improve(newton_update(f, df), near_zero)The reason why we define the function near_zero inside find_zero is to make it compatible with improve. Because the close argument is supposed to take in only one argument.

Now we can calculate the nth root:

def nth_root(n, a):

'''

>>> nth_root(3, 8)

2.0

'''

f = lambda x: pow(x, n)

df = lambda x: n * pow(x, n - 1)

return find_zero(f, df)One important application of HOFs is converting a function that takes multiple arguments into a chain of functions that each take a single argument. This is known as currying. For example, the function below converts the pow function into its curried form:

def curried_pow(x):

def h(y):

return pow(x, y)

return hSelf Reference

An interesting consequence of the way environment work is that a function can refer to its own name within its body. For example:

def print_sum(x):

print(x)

def add_next(y):

return print_sum(x + y)

return add_nextEvery time function print_sum being called, it will return add_next, in which x memorizes the previous sum. When add_next is looking for the value of x, it will look up to its parent frame, which is a feature of closure.

Closure

In programming languages, a closure, also lexical closure(词法闭包) or function closure(函数闭包), is a technique for implementing lexically scoped name binding in a language with first-class functions. Operationally, a closure is a record storing a function together with an environment. The environment is a mapping associating each free variable of the function (variables that are used locally, but defined in an enclosing scope) with the value or reference to which the name was bound when the closure was created. Unlike a plain function, a closure allows the function to access those captured variables through the closure's copies of their values or references, even when the function is invoked outside their scope.

Difference between eval and exec

eval accepts only a single expression, exec can take a code block that has Python statements: loops, try: except:, class and function/method definitions and so on.

An expression in Python is whatever you can have as the value in a variable assignment:

a_variable = (anything you can put within these parentheses is an expression)

eval returns the value of the given expression, whereas exec ignores the return value from its code, and always returns None.

Recursion

An interesting example from the lecture:

def cascade(n):

print(n)

if n >= 10:

cascade(n//10)

print(n)

def inverse_cascade(n):

grow(n)

print(n)

shrink(n)

def f_then_g(f, g, n):

if n:

f(n)

g(n)

grow = lambda n: f_then_g(grow, print, n // 10)

shrink = lambda n: f_then_g(print, shrink, n // 10)When using recursion, we should avoid redundancy. For example, in hw04, function min_depth is defined as follow:

def min_depth(t):

"""A simple function to return the distance between t's root and its closest leaf"""

if is_leaf(t):

return 0 # Base case---the distance between a node and itself is zero

h = float('inf') # Python's version of infinity

for b in branches(t):

if is_leaf(b): return 1 # !!!

h = min(h, 1 + min_depth(b))

return hIt still works without the line flagged with !!!, so we'd better remove this line to eliminate redundancy.

The example above is called arms-length recursion. Arms-length recursion is not only redundant but often complicates our code and obscures the functionality of recursive functions, making writing recursive functions much more difficult. We always want our recursive case to be handling one and only one recursive level. We may or may not be checking your code periodically for things like this.

Tree Recursion

Tree recursion appears whenever executing the body of a recursive function makes more than one recursive call. Tree recursion can be very time-consuming for it can be highly repetitive. Memoization is an extremely useful technique for speeding up the running time.

def memo(f):

cached = {}

def memoized(*args):

if args not in cache:

cache[args] = f(*args)

return cache[args]

return memoizedThe special syntax *args in function definitions is used to pass a variable number of arguments to a function. **kwargs has a similar effect. Look at the following examples to see how they differ.

def add(*args):

'''

Add the arguments and return the summation

Returns:

Summation of arguments

>>> add(1, 2, 3)

Data type of argument: <class 'tuple'>

6

'''

print("Data type of argument:", type(args))

return sum(args)

def intro(**kwargs):

'''

Print out introduction of a person

>>> intro(Firstname="Charles", Lastname="Wood", Age=22, Phone="+861008611")

Data type of argument: <class 'dict'>

Firstname is Charles

Lastname is Wood

Age is 22

Phone is +861008611

'''

print("Data type of argument:", type(kwargs))

for key, value in kwargs.items():

print("{} is {}".format(key, value))The parameter name does not have to be args or kwargs.

List

Sequence Unpacking

We have a nested list pair:

pairs = [[1, 2], [3, 4]]we can do:

for x, y in pairs:

...List Comprehension

Syntax:

[<map exp> for <name> in <iter exp> if <filter exp>]Pay attention to the square brackets!

Slicing

Slicing will create a new list, so when we need to copy a list lst, we can use lst[:] or list(lst).

When the slicing index is out of bound of list, it won't cause any trouble. Instead we'll get an empty list. (Unlike element selection, which will throw an IndexError)

Zip

The zip() function returns a zip object, which is an iterator of tuples where the first item in each passed iterator is paired together, and then the second item in each passed iterator are paired together etc.

If the passed iterators have different lengths, the iterator with the least items decides the length of the new iterator.

Debugging

assersion

Use assersion when you know a good invariant, which check that code meets an existing understanding.

Syntax: assert <exp>, 'Something goes wrong'

Doctest, Print debugging and Interactive debugging

Introduced before.

Error Types

SyntaxError

IndentationError

TypeError

xxx object is not callable: accidentally called a non-function as if it were a function.

NoneType: forgot return statement in a function

NameError or UnboundLocalError

A typo in the name in the description

Or Maybe shadowed a variable from the global frame in a local frame:

pythondef f(x): return x ** 2 def g(x): y = f(x) def f(): return y + x return f

Tracebacks

Components:

- The error message itself

- Lines #s on the way to the error

- What’s on those lines

Most recent call is at the bottom. Look at each line, bottom to top and see which one might be causing the error.

Trees

Abstraction

Recursive description (wooden trees)

- A tree has a root and a list of branches.

- Each branch is a tree.

- A tree with zero branches is called a leaf.

Relative description (family trees)

- Each location in a tree is called a node.

- Each node has a label value.

- One node can be the parent/child of another.

Implementation

def tree(label, branches=[]):

'''

>>> tree(3, [tree(1), tree(2, [tree(1), tree(1)])])

[3, [1], [2, [1], [1]]]

'''

for branch in branches:

assert is_tree(branch)

return [label] + list(branches)

def label(tree):

return tree[0]

def branches(tree):

return tree[1:]

def is_tree(tree):

if type(tree) != list or len(tree) < 1:

return False

for branch in branches(tree):

if not is_tree(branch):

return False

return True

def is_leaf(tree):

return not branches(tree)Tree Processing

We often use recursion to process a tree. Processing a leaf is often the base case of a tree processing function. The recursive case typically makes a recursive call on each branch, then aggregates.

Several built-in functions take iterable arguments and aggregate them into a value.

sum(iterable[, start]) -> valuestart has default value 0. Note that iterable doesn't have to be iterators. Lists and tuples are also iterable.

max(iterable[, key=func]) -> valuemax(a, b, c, ...[, key=func]) -> valueWith a single iterable argument, return its largest item.

With two or more arguments, return the largest argument.

all(iterable) -> boolReturn True if bool(x) is True for all values x in the iterable. If the iterable is empty, return True.

min,any(iterable) -> boolhas similar function.

For example:

def count_leaves(t):

'''Count the leaves of a tree.'''

if is_leaf(t):

return 1

else:

return sum([count_leaves(b) for b in branches(t)])A function that creates a tree from another tree is typically also recursive

def increment_leaves(t):

'''Return a tree like t but with leaf values incremented.'''

if is_leaf(t):

return tree(label(t) + 1)

else:

bs = [increment_leaves(b) for b in branches(t)]

return tree(label(t), bs)def increment(t):

'''Return a tree like t but with all node values incremented.'''

return tree(label(t) + 1, [increment(b) for b in branches(t)])increment doesn't have a base case, but it still works because when t is a leaf, branches(t) will be an empty list (slicing index out of range) and the recursion will stop automatically.

Mutation

Tuples

Tuples are Immutable Sequences, Immutable values are protected from mutation.

An immutable sequence may still change if it contains a mutable value as an element. For example:

s = ([1, 2], 3)

s[0] = 4 # Error

s[0][0] = 4 # OkSameness and Change

a = [10]

b = [10]

a == b # True (Equality, a and b evaluates to equal values)

a is b # False

a = b

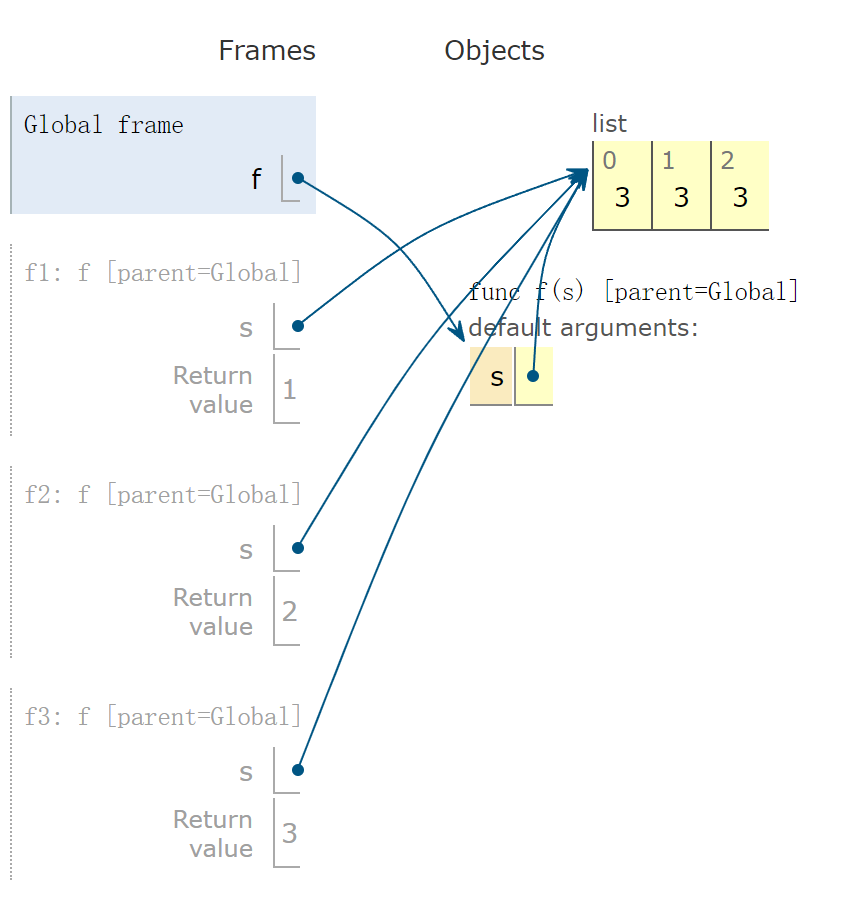

a is b # True (Identity, a and b evaluates to the same object)Mutable Default Arguments are Dangerous

A default argument value is part of a function value, not generated by a call:

def f(s=[]):

s.append(3)

return len(s)

f() # 1

f() # 2

f() # 3

Nonlocal Statements

Syntax: nonlocal <name>

Effect: Future assignments to that name change its pre-existing binding in the first non-local frame of the current environment in which that name is bound.

Names listed in a nonlocal statement must refer to pre-existing bindings in an enclosing scope.

Names listed in a nonlocal statement must not collide with pre-existing bindings in the local scope.

Mutable values can be changed without a nonlocal statement.

Iterators and Generators

Iterators

A container can provide an iterator that provides access to its elements in order.

iter(iterable): Return an iterator over the elements of an iterable value.

next(iterator): Return the next element in an iterator. Once an iterator has returned all the values in an iterable, subsequent calls to next on that iterable will result in a StopIteration exception.

Views of a Dictionary

A dictionary, its keys, its values, and its items are all iterable values.

An iterable value is any value that can be passed to iter to produce an iterator.

An iterator is returned from iter and can be passed to next; all iterators are mutable.

The order of items in a dictionary is the order in which they were added (Python 3.6+)

Historically, items appeared in an arbitrary order (Python 3.5 and earlier).

An dictionary object has methods keys, values and items. We can use them to iterate through a dictionary.

Built-in Functions for Iteration

Many built-in Python sequence operations return iterators that compute results lazily.

map(func, iterable): Iterate over func(x) for x in iterablefilter(func, iterable): Iterate over x in iterable if func(x)zip(first_iter, second_iter): Iterate over co-indexed (x, y) pairsreversed(sequence): Iterate over x in a sequence in reverse order

To view the contents of an iterator, place the resulting elements into a container:

- list(iterable): Create a list containing all x in iterable

- tuple(iterable): Create a tuple containing all x in iterable

- sorted(iterable): Create a sorted list containing x in iterable

Generators

A generator function is a function that yields values instead of returning them.

A normal function returns once; a generator function can yield multiple times.

When a generator function is called, it returns a generator object which is a type of iterator. This generator object iterates over its yields.

A yield from statement yields all values from an iterator or iterable.

def a_then_b(a, b):

for x in a:

yield x

for x in b:

yield x

# Using yield from

def a_then_b(a, b):

yield from a

yield from byield from also makes generators recursively yileds from itself like the recursion in normal functions:

def countdown(k):

if k > 0:

yield k

yield from countdown(k-1)Objects

Class Statements

When a class is called:

1.A new instance of that class is created:

2.The __init__ method of the class is called with the new object as its first argument (named self), along with any additional arguments provided in the call expression.

Methods

Methods are functions defined in the suite of a class statement. These def statements create function objects as always, but their names are bound as attributes of the class.

Every methods are defined with at least one arguments: self. Dot notation automatically supplies the first argument to a method.

Attributes

Using getattr, we can look up an attribute using a string

getattr(tom_account, 'balance') # 10

hasattr(tom_account, 'deposit') # Truegetattr and dot expressions look up a name in the same way.

Class attributes are "shared" across all instances of a class because they are attributes of the class, not the instance.

Instance attributes are set in __init__ method.

Inheritance

Syntax:

class <Name>(<Base Class>):

<suite>Conceptually, the new subclass inherits attributes of its base class.

The subclass may override certain inherited attributes.

Using inheritance, we implement a subclass by specifying its differences from the the base class.

Looking Up Attribute Names on Classes

To look up a name in a class:

- If it names an attribute in the class, return the attribute value.

- Otherwise, look up the name in the base class, if there is one.

Note that base class attributes aren't copied into subclasses!

Inheritance and Composition

Inheritance is best for representing "is-a" relationships.

E.g., a checking account is a specific type of account. So, CheckingAccount inherits from Account.

Composition is best for representing "has-a" relationships.

E.g., a bank has a collection of bank accounts it manages. So, A bank has a list of accounts as an attribute.

Linked List

class Link:

empty = ()

def __init__(self, first, rest=empty):

assert rest is Link.empty or isinstance(rest, Link)

self.first = first

self.rest = restProperty Methods

In some cases, we want the value of instance attributes to be computed on demand.

For example, if we want to access the second element of a linked list like this:

s = Link(1, Link(2, Link(3)))

s.second # Suppose to get 2

s.second = 6 # Can be modified by assignment

s # 1, 6, 3Of course we can add a second attribute to Link class, but the second element is stored in the linked list itself, so the best way is to make it behave like a function.

The @property decorator on a method designates that it will be called whenever it is looked up on an instance. A <attribute>.setter decorator on a method designates that it will be called whenever that attribute is assigned.

<attribute> must be an existing property method.

@property

def second(self):

return self.rest.first

@second.setter

def second(self, value):

self.rest.first = valueThese two functions will be called implicitly.

Interface

String Representations

An object value should behave like the kind of data it is meant to represent.

In Python, all objects produce two string representations:

- The

stris legible to humans - The

repris legible to the Python interpreter

The str and repr strings are often the same, but not always.

The repr function returns a Python expression (a string) that evaluates to an equal object. For most object types, eval(repr(object)) == object.

Some objects do not have a simple Python-readable string:

>>> repr(min)

'<built-in function min>'The result of calling str on the value of an expression is what Python prints using the print function.

Polymorphic Functions

Polymorphic function: A function that applies to many (poly) different forms (morph) of data.

str and repr are both polymorphic; they apply to any object.

repr invokes a zero-argument method __repr__ on its argument

str invokes a zero-argument method __str__ on its argument

def __repr__(self):

if self.rest is not Link.empty:

rest_repr = ', ' + repr(self.rest)

else:

rest_repr = ''

return 'Link(' + repr(self.first) + rest_repr + ')'

def __str__(self):

string = '<'

while self.rest is not Link.empty:

string += str(self.first) + ' '

self = self.rest

return string + str(self.first) + '>'repr and str can be implemented like this:

def repr(x):

return type(x).__repr__(x) # An instance attribute called __repr__ is ignored! Only class attributes are found

def str(x):

t = type(x)

if hasattr(t, '__str__'):

return t.__str__(x) # An instance attribute called __str__ is ignored

else:

return repr(x) # If no __str__ attribute is found, uses repr stringInterfaces

Message passing: Objects interact by looking up attributes on each other (passing messages)。

The attribute look-up rules allow different data types to respond to the same message.

A shared message (attribute name) that elicits similar behavior from different object.

Certain names are special because they have built-in behavior. These names always start and end with two underscores.

For example: __add__ method is invoked to add one object to another.

Adding instances of user-defined classes invokes either the __add__ or __radd__ method.

A polymorphic function might take two or more arguments of different types.

Type Dispatching: Inspect the type of an argument in order to select behavior.

Type Coercion: Convert one value to match the type of another.

class Ratio:

"""A mutable ratio.

>>> f = Ratio(9, 15)

>>> f

Ratio(9, 15)

>>> print(f)

9/15

>>> Ratio(1, 3) + Ratio(1, 6)

Ratio(1, 2)

>>> f + 1

Ratio(8, 5)

>>> 1 + f

Ratio(8, 5)

>>> 1.4 + f

2.0

"""

def __init__(self, n, d):

self.numer = n

self.denom = d

def __repr__(self):

return f'Ratio({self.numer}, {self.denom})'

def __str__(self):

return f'{self.numer}/{self.denom}'

def __add__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, int): # type dispatching

n = self.numer + self.denom

d = self.denom

elif isinstance(other, Ratio):

n = self.numer * other.denom + self.denom * other.numer

d = self.denom * other.denom

elif isinstance(other, float): # type coersion

return float(self) + other

g = gcd(n, d)

return Ratio(n // g, d // g)

__radd__ = __add__

def __float__(self):

return self.numer / self.denomTree class

class Tree:

def __init__(self, label, branches=[]):

self.label = label

for branch in branches:

assert isinstance(branch, Tree)

self.branches = list(branches)

def fib_tree(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return Tree(n)

else:

left = fib_tree(n-2)

right = fib_tree(n-1)

fib_n = left.label + right.label

return Tree(fib_n, [left, right])Modular design

A great example: restaurant search engine.

import json

def search(query, ranking=lambda r: -r.stars):

"""A restaurant search engine.

>>> results = search("Thai")

>>> results

[<Thai Basil Cuisine>, <Thai Noodle II>, <Jasmine Thai>, <Berkeley Thai House>, <Viengvilay Thai Cuisine>]

>>> for r in results:

... print(r.name, 'shares reviewers with', r.similar(3))

Thai Basil Cuisine shares reviewers with [<Gypsy's Trattoria Italiano>, <Top Dog>, <Smart Alec's Intelligent Food>]

Thai Noodle II shares reviewers with [<La Cascada Taqueria>, <Cafe Milano>, <Chinese Express>]

Jasmine Thai shares reviewers with [<Hummingbird Cafe>, <La Burrita 2>, <The Stuffed Inn>]

Berkeley Thai House shares reviewers with [<Smart Alec's Intelligent Food>, <Thai Basil Cuisine>, <Top Dog>]

Viengvilay Thai Cuisine shares reviewers with [<La Val's Pizza>, <Thai Basil Cuisine>, <La Burrita 2>]

"""

results = [r for r in Restaurant.all if query in r.name]

return sorted(results, key=ranking)

def num_shared_reviewers(restaurant, other):

return fast_overlap(restaurant.reviewers, other.reviewers)

# return len([r for r in restaurant.reviewers if r in other.reviewers])

def fast_overlap(s, t):

"""Return the overlap between sorted S and sorted T.

>>> fast_overlap([2, 3, 5, 6, 7], [1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8])

3

"""

count, i, j = 0, 0, 0

while i < len(s) and j < len(t):

if s[i] == t[j]:

count, i, j = count + 1, i + 1, j + 1

elif s[i] < t[j]:

i += 1

else:

j += 1

return count

class Restaurant:

"""A restaurant."""

all = []

def __init__(self, name, stars, reviewers):

self.name = name

self.stars = stars

self.reviewers = reviewers

Restaurant.all.append(self)

def similar(self, k, similarity=num_shared_reviewers):

"Return the K most similar restaurants to SELF, using SIMILARITY for comparison."

others = list(Restaurant.all)

others.remove(self)

return sorted(others, key=lambda r: -similarity(self, r))[:k]

def __repr__(self):

return '<' + self.name + '>'

def load_reviews(reviews_file):

reviewers_by_restaurant = {}

for line in open(reviews_file):

r = json.loads(line)

business_id = r['business_id']

if business_id not in reviewers_by_restaurant:

reviewers_by_restaurant[business_id] = []

reviewers_by_restaurant[business_id].append(r['user_id'])

return reviewers_by_restaurant

def load_restaurants(reviewers_by_restaurant, restaurants_file):

for line in open(restaurants_file):

b = json.loads(line)

reviewers = reviewers_by_restaurant.get(b['business_id'], [])

Restaurant(b['name'], b['stars'], sorted(reviewers))

load_restaurants(load_reviews('reviews.json'), 'restaurants.json')

while True:

print('>', end=' ')

results = search(input().strip())

for r in results:

print(r.name, 'shares reviewers with', r.similar(3))Sets

>>> s = {'one', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'four'}

>>> s

{'three', 'one', 'four', 'two'}

>>> 'three' in s

True

>>> len(s)

4

>>> s.union({'one', 'five'})

{'three', 'five', 'one', 'four', 'two'}

>>> s.intersection({'six', 'five', 'four', 'three'})

{'three', 'four'}

>>> s

{'three', 'one', 'four', 'two'}

13Scheme

Expressions

Atomic Expressions

Just like in Python, atomic, or primitive, expressions in Scheme take a single step to evaluate. These include numbers, booleans, symbols.

scm> 1234 ; integer

1234

scm> 123.4 ; real number

123.4Symbols

Out of these, the symbol type is the only one we didn't encounter in Python. A symbol acts a lot like a Python name, but not exactly. Specifically, a symbol in Scheme is also a type of value. On the other hand, in Python, names only serve as expressions; a Python expression can never evaluate to a name.

scm> quotient ; A name bound to a built-in procedure

#[quotient]

scm> 'quotient ; An expression that evaluates to a symbol

quotient

scm> 'hello-world!

hello-world!Booleans

In Scheme, all values except the special boolean value #f are interpreted as true values (unlike Python, where there are some false-y values like 0). Our particular version of the Scheme interpreter allows you to write True and False in place of #t and #f. This is not standard.

scm> #t

#t

scm> #f

#fCall expressions

Like Python, the operator in a Scheme call expression comes before all the operands. Unlike Python, the operator is included within the parentheses and the operands are separated by spaces rather than with commas. However, evaluation of a Scheme call expression follows the exact same rules as in Python:

- Evaluate the operator. It should evaluate to a procedure.

- Evaluate the operands, left to right.

- Apply the procedure to the evaluated operands.

Here are some examples using built-in procedures:

scm> (+ 1 2)

3

scm> (- 10 (/ 6 2))

7

scm> (modulo 35 4)

3

scm> (even? (quotient 45 2))

#tif Expressions

The if special form allows us to evaluate one of two expressions based on a predicate. It takes in two required arguments and an optional third argument:

(if <predicate> <if-true> [if-false])The Scheme if expression, given that it is an expression, evaluates to some value. However, the Python if statement simply directs the flow of the program.

Another difference between the two is that it's possible to add more lines of code into the suites of the Python if statement, while a Scheme if expression expects just a single expression for each of the true result and the false result.

One final difference is that in Scheme, you cannot write elif cases. If you want to have multiple cases using the if expression, you would need multiple branched if expressions.

cond Expressions

Using nested if expressions doesn't seem like a very practical way to take care of multiple cases. Instead, we can use the cond special form, a general conditional expression similar to a multi-clause if/elif/else conditional expression in Python. cond takes in an arbitrary number of arguments known as clauses. A clause is written as a list containing two expressions: (<p> <e>).

(cond

(<p1> <e1>)

(<p2> <e2>)

...

(<pn> <en>)

[(else <else-expression>)])The first expression in each clause is a predicate. The second expression in the clause is the return expression corresponding to its predicate. The optional else clause has no predicate.

The rules of evaluation are as follows:

- Evaluate the predicates

<p1>,<p2>, ...,<pn>in order until you reach one that evaluates to a truth-y value. - If you reach a predicate that evaluates to a truth-y value, evaluate and return the corresponding expression in the clause.

- If none of the predicates are truth-y and there is an

elseclause, evaluate and return<else-expression>.

Lists

Scheme lists are very similar to the linked lists. A Scheme list is constructed with a series of pairs, which are created with the constructor cons. It require that the cdr is either another list or nil, an empty list. A list is displayed in the interpreter as a sequence of values (similar to the __str__ representation of a Link object).

scm> (define a (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil)))) ; Assign the list to the name a

a

scm> a

(1 2 3)

scm> (car a)

1

scm> (cdr a)

(2 3)

scm> (car (cdr (cdr a)))

3There are a few other ways to create lists. The list procedure takes in an arbitrary number of arguments and constructs a list with the values of these arguments:

scm> (list 1 2 3)

(1 2 3)

scm> (list 1 (list 2 3) 4)

(1 (2 3) 4)

scm> (list (cons 1 (cons 2 nil)) 3 4)

((1 2) 3 4)Note that all of the operands in this expression are evaluated before being put into the resulting list.

We can also use the quote form to create a list, which will construct the exact list that is given. Unlike with the list procedure, the argument to ' is not evaluated.

scm> '(1 2 3)

(1 2 3)

scm> '(cons 1 2) ; Argument to quote is not evaluated

(cons 1 2)

scm> '(1 (2 3 4))

(1 (2 3 4))There are a few other built-in procedures in Scheme that are used for lists.

scm> (null? nil) ; Checks if a value is the empty list

True

scm> (append '(1 2 3) '(4 5 6)) ; Concatenates two lists

(1 2 3 4 5 6)

scm> (length '(1 2 3 4 5)) ; Returns the number of elements in a list

5Special Form

Define procedures

The special form define is used to define variables and functions in Scheme. There are two versions of the define special form. To define variables, we use the define form with the following syntax:

(define <name> <expression>)The rules to evaluate this expression are

- Evaluate the

<expression>. - Bind its value to the

<name>in the current frame. - Return

<name>.

The second version of define is used to define procedures:

(define (<name> <param1> <param2> ...) <body> )To evaluate this expression:

- Create a lambda procedure with the given parameters and

<body>. - Bind the procedure to the

<name>in the current frame. - Return

<name>.

The following two expressions are equivalent:

scm> (define foo (lambda (x y) (+ x y)))

foo

scm> (define (foo x y) (+ x y))

fooLambdas

All Scheme procedures are lambda procedures. To create a lambda procedure, we can use the lambda special form:

(lambda (<param1> <param2> ...) <body>)This expression will create and return a function with the given parameters and body, but it will not alter the current environment.

The function will simply return the value of the last expression in the body.

Quote and Quasiquote

The quote special form takes in a single operand. It returns this operand exactly as is, without evaluating it. Note that this special form can be used to return any value, not just a list.

Similarly, a quasiquote, denoted with a backtick symbol, returns an expression without evaluating it. However, parts of that expression can be unquoted, denoted using a comma, and those unquoted parts are evaluated.

=, eq?, equal?

=can only be used for comparing numbers.eq?behaves like == in Python for comparing two non-pairs (numbers, booleans, etc.). Otherwise, eq? behaves like is in Python.equal?compares pairs by determining if their cars are equal? and their cdrs are equal?(that is, they have the same contents). Otherwise, equal? behaves like eq?

Sierpinski's Triangle

(define (line len) (fd len))

(define (repeat k fn)

(fn)

(if (> k 1) (repeat (- k 1) fn)))

(define (pentagram len)

(repeat 5 (lambda () (line len) (rt 144))))

(define (tri fn)

(repeat 3 (lambda () (fn) (lt 120))))

(define (sier d len)

(tri (lambda () (if (= d 1) (fd len) (leg d len)))))

(define (leg d len)

(sier (- d 1) (/ len 2))

(penup) (fd len) (pendown))

(rt 90)

(speed 0)

(sier 6 400)Tail Recursion

Scheme implements tail-call optimization, which allows programmers to write recursive functions that use a constant amount of space. A tail call occurs when a function calls another function as its last action of the current frame. In this case, the frame is no longer needed, and we can remove it from memory. In other words, if this is the last thing you are going to do in a function call, we can reuse the current frame instead of making a new frame.

Consider this implementation of factorial.

(define (fact n)

(if (= n 0)

1

(* n (fact (- n 1)))))The recursive call occurs in the last line, but it is not the last expression evaluated. After calling (fact (- n 1)), the function still needs to multiply that result with n. The final expression that is evaluated is a call to the multiplication function, not fact itself. Therefore, the recursive call is not a tail call.

We can rewrite this function using a helper function that remembers the temporary product that we have calculated so far in each recursive step.

(define (fact n)

(define (fact-tail n result)

(if (= n 0)

result

(fact-tail (- n 1) (* n result))))

(fact-tail n 1))Tail context

When trying to identify whether a given function call within the body of a function is a tail call, we look for whether the call expression is in tail context. Given that each of the following expressions is the last expression in the body of the function, the following expressions are tail contexts:

- the second or third operand in an if expression

- any of the non-predicate sub-expressions in a cond expression (i.e. the second expression of each clause)

- the last operand in an and or an or expression

- the last operand in a begin expression’s body

- the last operand in a let expression’s body

Macros

scm> (define-macro (twice f) (list 'begin f f))

twicedefine-macro allows us to define what’s known as a macro, which is simply a way for us to combine unevaluated input expressions together into another expression. When we call macros, the operands are not evaluated, but rather are treated as Scheme data. This means that any operands that are call expressions or special form expression are treated like lists.

The rules for evaluating calls to macro procedures are:

- Evaluate operator

- Apply operator to unevaluated operands

- Evaluate the expression returned by the macro in the frame it was called in

Streams

Because cons is a regular procedure and both its operands must be evaluted before the pair is constructed, we cannot create an infinite sequence of integers using a Scheme list. Instead, our Scheme interpreter supports streams, which are lazy Scheme lists. The first element is represented explicitly, but the rest of the stream’s elements are computed only when needed. Computing a value only when it’s needed is also known as lazy evaluation.

We use the special form cons-stream to create a stream. To actually get the rest of the stream, we must call cdr-stream on it to force the promise to be evaluated.

Here’s a summary of what we just went over:

nilis the empty streamcons-streamconstructs a stream containing the value of the first operand and a promise to evaluate the second operandcarreturns the first element of the streamcdr-streamcomputes and returns the rest of stream

SQL

SQL is an example of a declarative programming language. Statements do not describe computations directly, but instead describe the desired result of some computation. It is the role of the query interpreter of the database system to plan and perform a computational process to produce such a result.

In SQL, data is organized into tables. A table has a fixed number of named columns. A row of the table represents a single data record and has one value for each column. Table used in examples below:

| Name | Division | Title | Salary | Supervisor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ben Bitdiddle | Computer | Wizard | 60000 | Oliver Warbucks |

| Alyssa P Hacker | Computer | Programmer | 40000 | Ben Bitdiddle |

| Cy D Fect | Computer | Programmer | 35000 | Ben Bitdiddle |

| Lem E Tweakit | Computer | Technician | 25000 | Ben Bitdiddle |

| Louis Reasoner | Computer | Programmer Trainee | 30000 | Alyssa P Hacker |

| Robert Cratchet | Administration | Big Wheel | 150000 | Oliver Warbucks |

| Eben Scrooge | Accounting | Chief Accountant | 75000 | Oliver Warbucks |

| Robert Cratchet | Accounting | Scrivener | 18000 | Eben Scrooge |

Creating Tables

We can use a SELECT statement to create tables. The following statement creates a table with a single row, with columns named “first" and ”last":

sqlite> SELECT "Ben" AS first, "Bitdiddle" AS last;

Ben|BitdiddleGiven two tables with the same number of columns, we can combine their rows into a larger table with UNION:

sqlite> SELECT "Ben" AS first, "Bitdiddle" AS last UNION

...> SELECT "Louis", "Reasoner";

Ben|Bitdiddle

Louis|ReasonerTo save a table, use CREATE TABLE and a name. Here we’re going to create the table of employees from the previous section and assign it to the name records:

sqlite> CREATE TABLE records AS

...> SELECT "Ben Bitdiddle" AS name, "Computer" AS division, "Wizard" AS title, 60000 AS salary, "Oliver Warbucks" AS supervisor UNION

...> SELECT "Alyssa P Hacker", "Computer", "Programmer", 40000, "Ben Bitdiddle" UNION ... ;We can SELECT specific values from an existing table using a FROM clause.

The special syntax SELECT * will select all columns from a table. It’s an easy way to print the contents of a table.

We can choose which columns to show in the first part of the SELECT, we can filter out rows using a WHERE clause, and sort the resulting rows with an ORDER BY clause (In non-decreasing order by default).

In general the syntax is:

SELECT [columns] FROM [tables]

WHERE [condition] ORDER BY [criteria];Note that all valid SQL statements must be terminated by a semicolon (😉. Additionally, you can split up your statement over many lines and add as much whitespace as you want, much like Scheme.

Joins

Data are combined by joining multiple tables together into one, a fundamental operation in database systems. There are many methods of joining, all closely related, but we will focus on just one method (the inner join) in this class. When tables are joined, the resulting table contains a new row for each combination of rows in the input tables. If two tables are joined and the left table has m rows and the right table has n rows, then the joined table will have mn rows. Joins are expressed in SQL by separating table names by commas in the FROM clause of a SELECT statement.

SQL allows us to join a table with itself by giving aliases to tables within a FROM clause using the keyword AS and to refer to a column within a particular table using a dot expression. In the example below we find the name and title of Louis Reasoner’s supervisor.

sqlite> SELECT b.name, b.title FROM records AS a, records AS b

...> WHERE a.name = "Louis Reasoner" AND a.supervisor = b.name;

Alyssa P Hacker | ProgrammerAggregation

We can use the MAX, MIN, COUNT, and SUM functions to retrieve more information from our initial tables.

If we wanted to find the name and salary of the employee who makes the most money, we might say

sqlite> SELECT name, MAX(salary) FROM records;

Oliver Warbucks|150000Using the special COUNT(*) syntax, we can count the number of rows in our table to see the number of employees at the company.

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(*) from RECORDS;

9These commands can be performed on specific sets of rows in our table by using the GROUP BY [column name] clause. This clause takes all of the rows that have the same value in column name and groups them together.

We can find the miniumum salary earned in each division of the company.

sqlite> SELECT division, MIN(salary) FROM records GROUP BY division;

Computer|25000

Administration|25000

Accounting|18000These groupings can be additionally filtered by the HAVING clause. In contrast to the WHERE clause, which filters out rows, the HAVING clause filters out entire groups.

To find all titles that are held by more than one person, we say

sqlite> SELECT title FROM records GROUP BY title HAVING count(*) > 1;

ProgrammerCreate Table and Drop Table

Create Empty Table:

CREATE TABLE numbers(n, note);

CREATE TABLE numbers(n UNIQUE, note);

CREATE TABLE numbers(n, note DEFAULT "No Comment");Drop Table:

DROP TABLE [IF EXISTS] numbers;Modifying Tables

INSERT

For a table t with two columns, to insert into one column:

INSERT INTO t(column) VALUES(value);To insert into both columns:

INSERT INTO t VALUES(value0, value1);UPDATE

Update sets all entries in certain columns to new values, just for some subset of rows.

UPDATE numbers SET n = 0 WHERE note = "No Comment";DELETE

Delete removes some or all rows from a table.

DELETE FROM numbers WHERE n = 0;